All archaeology students want to know how their degree is going to translate into a gainful employment. Millennials and Gen-Z are as pragmatic as they are impatient. More than previous generations, I feel like they want to know exactly how each action is going to benefit their own personal goals and they want to know it from the outset. This is why it works well to show them exactly how to get from Point A to Point B and what they can expect when they get to Point B.

Today’s youth are willing to work extremely hard if they think the result will help them achieve their goals. I also feel like anthropology enrollments will grow if students know they can get a part-time job through the department that contributes directly to their career path before they graduate. Both departments and students will benefit from knowing what types of jobs students get after graduation (Cultural resource management companies, take note. Jobs with benefits is what everyone is looking for. Most of us are willing to take a median pay rate as long as we get medical/dental/vision and retirement. Lack of benefits is a serious reason for attrition among CRM archaeologists.)

This is a continuation from a previous post that you can visit here: (http://www.succinctresearch.com/the-archaeological-field-school-system-is-broken-part-i/). If you read that post, you will see my own personal assessment of the problems archaeologists and universities are having creating fruitful field school that have the potential to connect with BIPOC and other non-traditional students. Here I’d like to talk about my own suggestion for a solution.

There are very few departments that show students a clear pathway to employment even though every undergrad is looking exactly for that. In my previous post, I outlined the reasons why field schools are not conducive to maintaining CRM as an industry. Let’s look at one possible solution.

Solution #1: Paid CRM Internships

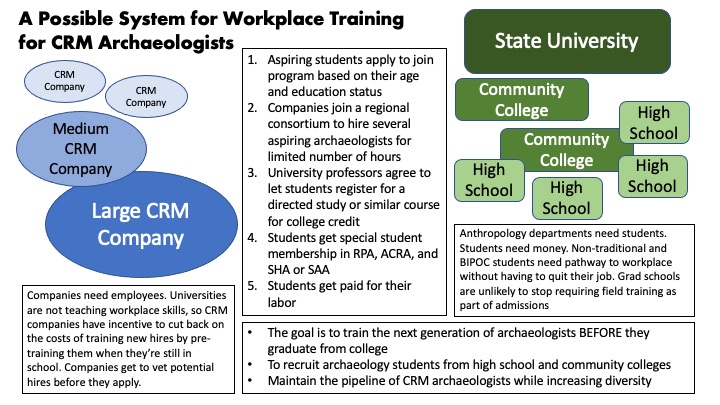

There are already CRM-university collaborations designed to provide workplace training for aspiring CRMers. Here’s an example. Here’s another one. Here’s yet another one. There are ones I don’t know about. The key is we can use these existing initiatives to guide future actions.

I’m suggesting two things:

1) Increase public-private archaeology training collaborations and,

2) Consider substituting a paid, professional development internship for a traditional field school.

We could create a system where select students are hired to work part time for local CRM companies BEFORE they graduate or even have a field school. Taking the best of what I’ve seen so far, here’s a strategy that could work:

1) Recruit students who want to become archaeologists and can do archaeological work. Depending on where you live, these folks need to be at least 16 years old and legal to work. The easiest place to recruit candidates is through universities that teach archaeology (community colleges and universities), but there are some high schools who have connections to anthropology departments and could tell their students about this opportunity.

Unfortunately, my idea leaves out a number of foreign students and immigrant students who do not have visas or documents to work in the United States. This could still work in places like California, where I live, because employers and universities tend to uphold the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) that provides mechanisms for immigrants who arrived as children to legally work and attend school. I am unsure as to how we could include these folks in anti-immigrant states.

This part will depend on university professors who understand the reality that their students are most likely to go into CRM if they want to become archaeologists. Professors need to clearly communicate this reality to students who are interested in doing archaeology for a living. This will also require professors to teach directed study courses so students can get university credit for the internship. These directed studies are extra work. They probably won’t count towards tenure, but definitely should be considered a form of service, especially if you dovetail your efforts with those of an on-campus organization like the career center, vocational training, or DEI department.

2) Find CRM companies willing to participate in the program. Companies are going to have to have the money and capacity to train and supervise these interns. They also must have work those interns can do. Most importantly, they need to take this seriously. It’s going to take an investment in time and money, but it is much cheaper than the current way new hires are trained in CRM archaeology.

3) Find an archaeology organization give the program legitimacy. Someone has to give this whole thing enough legitimacy that other employers will recognize that it is equivalent to the traditional archaeological field school. The Register of Professional Archaeologists (RPA) is a prime candidate even though this benefits American Cultural Resources Association (ACRA) members the most.

In a perfect world, the RPA could levy some sort of “accreditation” to companies or regional consortiums that agree to participate in the program. The sanction of a professional organization helps convey a level of legitimacy to the entire thing and could establish a criterion of minimum hours for field tech tasks while also recognizing the regional differences in how CRM archaeology is conducted.

The whole “accreditation” thing would revolve around the three main tasks CRM companies already think is happening in field schools:

1) Learning field methods: This means the act of removing sediments in a controlled manner and pedestrian survey as much as it does performing backbreaking manual labor in the elements.

2) Identifying artifacts: We believe field school students will encounter lithics, groundstone, ceramics, metal, glass, and other sorts of portable human-made item found in an archaeological context, and are learning how to distinguish them from regular rocks or modern garbage.

3) Becoming a professional: This includes recordation practices as much as it does how to handle oneself around other people, how to interpret archaeological features, occupational health and safety, anti-harassment, anti-racism, ect. All the things 21st century employers universally expect from their employees.

I also suggest internship participants get some free organizational memberships so they have access to networking opportunities. For example, the RPA has a student rate. This could be waived for interns in hopes that they will become paying members after they graduate. It would be even better if interns also got membership in their local archaeology organization and another national one (Society for American Archaeology [SAA], Society for Historical Archaeology [SHA], or American Institute for Archaeology [AIA]). This would further connect interns to the wider professional and scholarly field, which hopefully would pique their interest even more, enough to get them addicted to archaeology for life. It would also give them opportunities to interact with the folks who could hire them someday.

The proposed accreditation is an essential element to make this program recognized as comparable to field school because we are asking archaeologists to rethink something that is considered essential to becoming a professional archaeologist. Having a field school is required for many government jobs and CRM companies. There has to be some sort of mechanism for demonstrating legitimacy. Endorsement by professional organizations could suffice.

4) Create the program. Give it a name, promote it in local universities, and inform CRM company directors that this is going to happen. This will also require companies and universities to decide upon a given number of hours interns will work and a range of tasks they will do. Companies will have to work amongst themselves to make sure interns aren’t getting overworked or neglected. The program will work best if interns are given exposure to more than one company so they can see differences in workplace culture and build their professional network by meeting more people. Pooling resources will also make it more financially feasible since multiple companies are paying paychecks rather than a single company footing the bill.

In a nutshell, companies will hire interns as part-time employees and give them the kind of tasks that will provide an introductory experience to what they will be expected to do as a field tech. The program will show interns the kinds of things that take place in CRM so they have a better idea as to what classes they need to take in college and how they’d like to specialize their skills. Depending on the company interns would be expected to do archaeological survey (shovel probes or pedestrian survey), taking GIS points, data collection, photography, artifact processing, tabulating previous research and/or sites in project area, organize company library, caring for field equipment, maintaining vehicles, copying/scanning, and the other tasks field techs do. Building upon what we learned during COVID-19 “shelter-in-place,” we know we can devise options for hybrid work with some activities done outside the office. This will require supervision but could still result in productive experiences.

The program criteria could say something like, “In 6 months, each intern in this program will spend at least one day surveying, one day monitoring, and one day working in an archaeological lab under the supervision of a qualified CRM archaeologist. They will also spend at least one day working in-person in an office doing whatever tasks an entry level field tech could be expected to do (taking care of field equipment, scanning documents, cleaning trucks, working with databases ect.).” Of course, the interns would have to spend more than an 8-hour day doing each of those tasks to be able to proficiently conduct 8 solid hours doing them, which is why the whole program would be something like 96 hours spent over the entire 6 months, or 16 hrs./month across 6 months. This is less than half of what a student would spend doing archaeology if they attended a 4-week field school and way less than what they’d encounter on a 6-week field school, so, depending on the company, you could require folks to do more than one of these internships before graduation. In the course of this sort of program, it’s likely interns would encounter most of what a field tech normally does on the job and they would have met dozens of archaeologists along the way. It is also likely students could find themselves working in the field, lab, or office for companies on short projects and complete the entire 96 hours in less than 6 months. For example, a week of survey over spring break would cover 40 hours of the internship. Or, two months of doing monitoring under the supervision of another archaeologist for 10-hour days on the weekends could cover 80 hours of the internship; the remainder could easily be attained in the remaining 4 months.

The key is to start small and scale the program up. I recommend 2 to 4 interns in a given region to start. This will be just enough to see if the program works and decide if it can be expanded. I’d love it if, eventually, this becomes a regional apprenticeship program for CRMers that can fulfill all the staffing needs for the whole area. Field school can remain what it is, a cool experiential learning class for those who can afford it, but the internship program could become a major benefit to a career in archaeology.

5) Revise and refine. There needs to be some sort of mechanism for refining the process. As part of their directed study, students will meet with their advising professor to talk about their internships. Students will also have to show evidence of work and talk about what they’re learning and what they wish they were learning. This info is communicated to company so both parties can adjust the internship. Companies will also want to evaluate the interns’ performance on the job so they can better coordinate future interns and/or make job offers to the interns they want to hire as field techs.

Again, this whole process would work best if multiple companies in a region worked with students. Places like the San Francisco Bay Area, southern Arizona, the Boston metro area, Washington D.C., and similar metropolitan areas are very suitable for this idea because there are lots of CRM companies and universities in proximity. Also, these metropolitan areas are in municipalities with multiple layers of protections in place for historic properties so there is comparatively more work for interns to do. Working across companies would also help students learn more about the idiosyncratic preservation regulations in their region or state.

One Example Scenario

Here’s an example of how this could have worked for an undergraduate like me, someone who really wanted to become an archaeologist but lives in the 2020s in a city where this program exists.

As mentioned in the previous post, I already worked 30+ hours each week but I could have fit in a couple hours of work in the evening as well as a few 10-hour days each month. I could have worked remotely on tables, figures lists, doing QA on digital forms recorded by crews in the field, collating photo logs and things like that. My hours worked would be recorded on a laptop or iPad issued to me at the start of the internship as I’d have to log into the company servers or Microsoft Teams groups where my activities would be recorded by each company. Of course, I would also have meetings (virtual or in person) with my supervisor(s) who would tell me what I needed to do for what project and how long I had to do it. My course and work schedule could also be shared with the companies in the consortium, so they know not to schedule me when I had school or my other jobs. With proper lead time, I could have adjusted the hours of my main hustle to accommodate some full 8-hour days working at the company office or going in the field as a paid job shadow.

The real boost in experience would come when I was working in the field surveying, monitoring, or excavating as a job shadow. It would probably only be single days at a time or weekends but if I showed aptitude I might have been offered opportunities to work full time on projects for entire weeks at a time. One week of full-time work during the winter break, spring break, or summer vacation would cover huge chunks of my entire internship obligation and supplement my income. Best of all, this wouldn’t be a field school (e.g. another college class). It would be actual workplace experience for real CRM companies doing real CRM archaeology, gainful employment that fills a valuable space on my resume.

Lastly, part of this time would be spent meeting with my faculty advisor where I would show them what I’d been up to and how I feel about the program. There might also be a written essay or some other sort of product to appease the curriculum gods if I was trying to get credits for this as an independent study.

In sum, the entire experience would give me an excellent idea as to what CRM archaeology is all about, I’d get prevailing wages for my labor (possibly per diem sometimes), but, most importantly, I would be demonstrating my skills, abilities, and willingness to work to several different companies. This eases many of the problems companies are having hiring folks while also training incoming field techs in modern CRM archaeological field methods and making the transition from the classroom to the workplace much easier.

Another Added Benefit: A Candid Evaluation of the CRM Industry

The interviews with interns have the potential to provide a candid look at the CRM industry. It will give us an idea as to why more students don’t want to do CRM. The best thing that could happen from this program is:

- Professors could find the students, approve the college credits, and do the mentorship.

- CRM companies could administer the internship, pay the interns, and give them workplace experience.

- Interns complete the entire program, give their feedback, and.

- Most of them decide they don’t want to do CRM. They all turn us down because they decide they don’t like how CRMers are treated.

This could be seen as a failure, but it would expose the most glaring problem with being a professional archaeologist in the United States today: It’s not a job that is conducive to living a well-adjusted, comfortable, engaged adult life.

The reason why there is so much attrition in the industry is because the industry doesn’t take care of its employees at any level. Academia is not much better, but I’ve talked to folks who tell me the shelf life for a CRM archaeologist isn’t much longer than 5 years. The SEAC survey described in Meyers et al. (2018) shows women drop out of the industry at an alarming rate in their 30s, which is right around the time that they have the 10+ years of experience necessary to rise to the highest levels. The authors explain that the endemic sexual harassment women in archaeology face is a major contributing factor to their attrition, but CRM has long been an uncomfortable place for mothers. I’ve written about it here.

If we created an internship/apprenticeship program and a number of the participants decided they didn’t want to do CRM after all it would show us that there are major structural problems with the industry itself. That might give us the information necessary to make changes. However, we will never figure that out by surveying all the folks with a graduate degree who are currently archaeology careerists, which is what the survey data from organizations like the SAA and RPA currently do. Careerists are already invested in this. They’ve got a grad degree and have devoted much of their lives to archaeology. It is hard for someone this invested in their career to say that they have doubts about continuing in the industry.

The situation is different for someone starting out on the ground floor. Entry-level field techs have an entirely different perspective on CRM. They’re looking at the people around them and thinking, “Do I really want to be like that when I’m their age?” We know that it only takes a few years for many technicians realize archaeology is not for them. It’s never too late to change careers; however, it is much easier to change directions before you’ve finished your degree. Rethinking your career is painful if you’ve already gotten a college degree in something you don’t enjoy doing. In our current system, we’re asking archaeologists to get their degree before they even know if archaeology is what they want to do and we’re finding out that many new technicians decide to go another direction within a few years. This is tragic on so many levels and, from a certain point of view, it’s predatory and unethical.

I believe changing the archaeological field school system could be a mechanism for reforming university departments and the cultural resource management archaeology industry. CRM companies will be better off training students before they graduate. It is clear that universities cannot do this for the industry. Demonstrating a clear pathway towards employment is something students really want to see. Anthropology departments will benefit from showing exactly what you can do with an anthropology degree, which includes CRM archaeology among other things. Getting workplace experience while you go to college is attractive to many archaeology students and a paid internship with local companies makes it possible without universities having to find the money from their existing budgets that basically prohibit paying anyone except PhD students.

Most importantly, the next generation of archaeological field technicians will have a better understanding of what they’re getting themselves into at an earlier stage in their career. They’ll get a chance to do archaeology before finishing their degree and they’ll have another option to archaeological field school. This program will be attractive to all students but have a better chance of reaching working-class, BIPOC, student parents, and non-traditional students. In our existing system, these students are being asked to risk the wellbeing of their families and themselves to take a gamble on being an archaeologist. This is something we can no longer ask, especially if we want to diversify the field.

In the process of creating this program, archaeology will learn a lot about itself. It will be an introspective voyage that will ask us to rethink concepts at the very core of what it means to be a professional archaeologist. We will have to examine the value field school brings to the profession as well as think about what the profession is doing to us as human beings. Transformation is at the core of this proposal. I am not saying we need to get rid of traditional archaeological field schools. I’m saying we can start a new tradition.

Write a comment below or send me an email.

Having trouble finding work in cultural resource management archaeology? Still blindly mailing out resumes and waiting for a response? Has your archaeology career plateaued and you don’t know what to do about it? Download a copy of the new book “Becoming an Archaeologist: Crafting a Career in Cultural Resource Management” Click here to learn more.

Having trouble finding work in cultural resource management archaeology? Still blindly mailing out resumes and waiting for a response? Has your archaeology career plateaued and you don’t know what to do about it? Download a copy of the new book “Becoming an Archaeologist: Crafting a Career in Cultural Resource Management” Click here to learn more.

Check out Succinct Research’s contribution to Blogging Archaeology. Full of amazing information about how blogging is revolutionizing archaeology publishing. For a limited time you can GRAB A COPY FOR FREE!!!! Click Here

“Resume-Writing for Archaeologists” is now available on Amazon.com. Click Here and get detailed instructions on how you can land a job in CRM archaeology today!

“Resume-Writing for Archaeologists” is now available on Amazon.com. Click Here and get detailed instructions on how you can land a job in CRM archaeology today!

Small Archaeology Project Management is now on the Kindle Store. Over 300 copies were sold in the first month! Click Here and see what the buzz is all about.

Small Archaeology Project Management is now on the Kindle Store. Over 300 copies were sold in the first month! Click Here and see what the buzz is all about.

Join the Succinct Research email list and receive additional information on the CRM and heritage conservation field.

Get killer information about the CRM archaeology industry and historic preservation.