Sometimes I wonder what I could see if I were invisible and had a time machine. Just a ghost that could travel through time and sit back to observe people as they do what they do. They couldn’t see me but I could see them. I wonder what I would see?

Sometimes I wonder what I could see if I were invisible and had a time machine. Just a ghost that could travel through time and sit back to observe people as they do what they do. They couldn’t see me but I could see them. I wonder what I would see?

Imagine this. The year is 1825 A.D. You’re on the Rocky Mountain front in what is now northern Montana just across the border from Canada. As an invisible observer, you witness a small band of Blackfeet Indians traversing the prairie landscape. They set up camp near an intermittent stream. Children play near women who are setting up teepees. Younger men, typically a nuisance to the hard working women, are making plans to set up a small hunting camp about a mile north of the main camp where they could take care of their horses while, hopefully, taking some game. The group is about to split off. Which group would you follow to watch?

In a flash, you are transported to Fort Boise in Idaho. The year is 1878. It’s the Fourth of July. On the parade grounds, U.S. Army soldiers stand at attention in the parade ground. They’re listening to a speech on freedom, justice, and liberty given by the base commander. It’s hot but the small Euroamerican population of the fledgling town of Boise has all come out to see the parade and watch the fort’s cannon give a celebratory blast. They sit near the parade grounds on blankets near picnic baskets. As the speech continues, you notice a small group of Shoshone walking around at the base of the hill below the parade ground. You wonder how they feel about Euroamerican freedom and justice. As you’re about to leave, you also spy a young boy sitting near the cannon with rapt attention. He’s waiting for that blast with the concentration of a cheetah. Do you stick around to see what the boy does when the cannon fires?

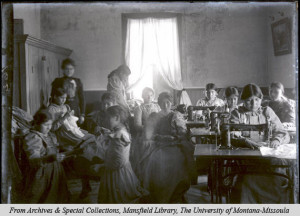

Now it’s December, 1914. You’re still in Montana but you’re now near Browning. From your ghost-eye-view you watch two boys, 6 and 7-years-old, walk through shallow snow drifts towards a dairy barn. You’re at an Indian boarding school operated by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. It’s mid-morning and the boys should be in class learning how to read but they’ve been told to go milk the cows for lunch. Nobody has shown these boys how to milk a cow. They’ve just got a bucket and some ideas. Even though they’re young, they are attentive to their task. Goofing off is likely to earn them a stern punishment. The boys get to the barn and start “milking” the cow. It has little milk since the children are in charge of taking care of the dairy cows even though they’ve never been shown how to do so. Their efforts get them very little results. The bucket is almost empty. As they stand to leave, you notice the boys don’t have shoes on. Their little feet are discolored from the cold. Do you stay and keep watching or move on from this tragedy?

Community-Based Participatory Research of the Mundane Past

Those are among the storylines of the sites I volunteered and worked at in the weeks leading up to the 2016 #dayofarch. Each of them were a form of community-based participatory research in the fact that they included community members in the data collection process and/or were prompted by community interest. In May, 2016, I helped record oral histories with Blackfeet Tribal members at a series of prehistoric and protohistoric sites in Toole County, Montana. This area had cultural association with the famous petroglyph site Writing-on-Stone in Alberta, Canada and the Sweetgrass Hills in Montana. Tribal consultants described how these sites played an important role in the yearly transhumance cycle of the Blackfeet before they were forced on the reservation.

In July, 2016, I went back to the Blackfeet Reservation to help record buildings and historical archaeological features at the Cut Bank Boarding School in Glacier County, Montana. Consultants described the formative role the school played in their lives; however, archival documents suggest early students were forced to experience extreme deprivation. The struggles of students during the early 1900s led to a more functional and humane facility by the 1930s.

Finally, I volunteered at the Fort Boise Archaeology Project in Boise, Idaho in late July, 2016. Sponsored by the University of Idaho, the project focused on compliance excavations in the former fort’s parade grounds. The local community was once again invited to participate in the excavations as they were during last year’s River Street Archaeology Project.

Each of these projects involved the community and is rooted in the ethos of community-based archaeology at some level. The Blackfeet are active participants in the history-making process in their ancestral territories. The community in Boise is used to participating in archaeological excavations. The University of Idaho and other institutions foster and promote including local residents and university students in archaeology.

The goal of community-based archaeology is addressing the questions that count for local people. Each of these projects contributes to that goal.

The boarding school experience shaped Native American lives

The boarding school experience shaped Native American lives

From 1906 until the 1950s, the Cut Bank Boarding School in Glacier County, Montana was reportedly a vehicle for teaching Blackfeet children what they needed to survive in a non-Native world. By this time, the buffalo herds that supported the people had all been destroyed. The Blackfeet were starving. Sending their children to an institution where they had a chance to get three square meals a day appealed to many families on the reservation.

Kids as young as 5-years-old were eligible to attend the school. Families of young students frequently camped near the boarding school. Older children left their families behind only to see them on holiday breaks. The children were responsible for growing their own food. They managed a large garden, raised cattle, and milked cows to support the school. Unfortunately, unscrupulous principals and Indian agents pilfered school funds and sold the school’s produce. The children were left without shoes or enough to eat.

The situation got so bad that it prompted a congressional investigation was launched in 1914. The investigators witnessed starving children with insufficient clothing trying to take care of cattle in the Montana winter. Teachers were unqualified and lessons were insufficient. Students told the investigators they simply wished to get enough to eat.

After the congressional investigation, many of the school’s administrators lost their jobs. The Bureau of Indian Affairs reorganized the school and improved its facilities in the following years. By the 1950s, Blackfeet informants remarked that the school was functional and useful for many families. The goal of the boarding school system was to destroy Native American culture by inculcating them in Euroamerican cultural mores. This worked somewhat, but education was not able to completely eradicate Native beliefs and ways of being.

From the 1930s to 1950s, the Cut Bank Boarding School provided a stable environment where hard work and study was rewarded with food, clothing, and board. Consultants remarked that the education they received went beyond book learning and included values, punctuality, and agricultural or domestic skills. The former students I spoke with said the school played a formative role in the way they lived their lives as adults. While they remained firmly rooted in Blackfeet cultural beliefs, these consultants said the reformed boarding school helped teach students life skills that would help them be socially responsible adults.

The story of the boarding school experience is very complicated. These instructions were created in order to destroy Native culture. Mismanaged ones like the early days at the Cut Bank School forced students to endure horrible conditions. At other boarding schools, children regularly died under the supervision of school administrators. This was not the case at Cut Bank, but it almost became that way. Former students are aware of the way these boarding schools were attempting to acculturate them to Euroamerican society. Fortunately, many students were able to maintain their cultural beliefs while also learning the way of the white people. The only way archaeology can write the complex story of boarding schools is by including descendant communities in the translation of these archaeological remains.

Rock rings tell the story of bygone days

Rock rings tell the story of bygone days

Sometimes historical archaeologists are easy to dismiss prehistoric features. For people like me, who are intimately familiar with identifying features and sites on historical maps or in records, it can be an exercise in creativity to notice ephemeral prehistoric archaeological features. Some features are even difficult for prehistoric archaeologists to identify. Including descendant communities in the interpretation and identification of culturally unique archaeological features is one of the most fruitful ways for archaeologists to interpret complicated and ephemeral archaeological resources.

Archaeological sites are part of landscapes. Features are also part of a culturally specific system that is logical to members of those systems but can remain unknown or misunderstood by outsiders. Since landscapes are rooted in culture, the location, design, and geography of archaeological sites is best understood in terms of the way they contribute to landscapes. One of the only ways we can interpret these culturally specific landscapes is by including descendant communities in their identification and interpretation.

The Blackfeet Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) has been active in local cultural resource management archaeology. They have conducted a number of CRM projects and consistently employ tribal archaeologist on local CRM projects conducted by other companies. There are myriad benefits for including tribal archaeologists in local CRM, but the best benefit is their command of Native American culture. In my experience, Native American archaeologists see the past differently than non-Native do—especially when it comes to sites in their traditional culture area. While it is possible for non-Natives to comprehend the Native American worldview, it is not possible to understand it in the same way as a Native person.

I recently visited a number of prehistoric archaeological sites with Blackfeet consultants this May as part of a CRM project that had an oral history component. This experience helped me realize prehistoric sites are part of larger landscapes. There are no archaeological “sites,” only landscapes that contain the material remains of past activities. We call theses remains archaeological sites but, as they were seen by prehistoric people, these sites have no boundaries because they exist on culturally created landscapes.

Every feature has a reason. Every site is placed based on a logical understanding of natural and spiritual resources. The whole thing is interrelated.

For decades I have been thinking about sites as cultural resources; discretely defined loci of activity. It’s hard to get out of that mindset, but I never would have done so without my experience of visiting rock rings in northern Montana with Blackfeet consultants.

From Parade Ground to Parking Lot

I have never known ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to work in an urban environment. I always wonder why Bluestake and other utilities locating services can accurately locate all sorts of fiber optic, gas, sewer, and electric lines but we rarely locate historical archaeological features using GPR. (P.S. If you know why, please tell me. I’d like for GPR to work on historical sites but have had no success. Email or write a comment below if you have any suggestions.)

The University of Idaho has a track record of conducting public archaeology projects in Boise during the summer. This year, they returned to the grounds of Fort Boise to conduct excavations in advance of a construction project. I was fortunate to volunteer with college students and other local Boiseans at the excavations. The avocational and volunteer archaeology community in Boise is very active and interested in doing archaeological work. They showed up in full force for the summer dig and helped make it a success.

Prior to the excavations, a comprehensive GPR and metal detector program was conducted across the entire project area. It resulted in identifying hundreds of “anomalies” including architectural debris, buttons, ammunition, and other artifacts. The project included a ground-proofing element along with controlled excavation units located on larger anomalies that may be buried features.

This is the second time I’ve helped with public archaeology in Boise. The best thing about working there, aside from getting to see my mom, is the wellspring of involvement from the local community. People care about archaeology here and they are willing to trade their time to sweat in the 100+-degree sun in order to be part of public projects. It has taken years for the University of Idaho and other archaeology organizations to cultivate this involved public, but we can see the returns today.

Community-Based Participatory Research is how we will keep archaeology from becoming irrelevant

This morning I read an article called “Why social science risks irrelevance.” The piece concludes with the statement, “In essence, we need to be accountable for the privilege we have to pursue knowledge. And with that privilege, we need to stop lamenting how the public doesn’t understand or respect our work and start using our social-scientific knowledge to truly understand and appreciate why.”

I feel like this conclusion falls short of what the social science really need. What all social sciences need to do is:

1) Involve communities in our practice

2) Spend more time (a lot more time) talking with communities about the findings of our work and why this matters to community members

3) Whenever possible, do work that matters to local communities.

There is no way any of this can happen without conducting research that is rooted in communities.

Cultural resource management archaeology is detached from communities because of our obligations to our clients. But, when the work is done and it enters the public domain (i.e. state historic preservation office [SHPO]), we need to double our efforts to share the fruits of our work with the communities for which the work was conducted. Stories like the ones I shared at the beginning of this blog post are an excellent way to connect with communities and get them interested in our work. These stories come from working with descendants and crafting archaeological narratives in order to better understand the past. Grounding our work in communities is the only way we can keep from becoming irrelevant. This is my message for Day of Archaeology 2016.

Write a comment below or send me an email.

Having trouble finding work in cultural resource management archaeology? Still blindly mailing out resumes and waiting for a response? Has your archaeology career plateaued and you don’t know what to do about it? Download a copy of the new book “Becoming an Archaeologist: Crafting a Career in Cultural Resource Management” Click here to learn more.

Having trouble finding work in cultural resource management archaeology? Still blindly mailing out resumes and waiting for a response? Has your archaeology career plateaued and you don’t know what to do about it? Download a copy of the new book “Becoming an Archaeologist: Crafting a Career in Cultural Resource Management” Click here to learn more.

Check out Succinct Research’s contribution to Blogging Archaeology. Full of amazing information about how blogging is revolutionizing archaeology publishing. For a limited time you can GRAB A COPY FOR FREE!!!! Click Here

“Resume-Writing for Archaeologists” is now available on Amazon.com. Click Here and get detailed instructions on how you can land a job in CRM archaeology today!

“Resume-Writing for Archaeologists” is now available on Amazon.com. Click Here and get detailed instructions on how you can land a job in CRM archaeology today!

Small Archaeology Project Management is now on the Kindle Store. Over 300 copies were sold in the first month! Click Here and see what the buzz is all about.

Small Archaeology Project Management is now on the Kindle Store. Over 300 copies were sold in the first month! Click Here and see what the buzz is all about.

Join the Succinct Research email list and receive additional information on the CRM and heritage conservation field.

Get killer information about the CRM archaeology industry and historic preservation.