(In Part 1 of this series, I discussed how the field of archaeology is negatively affected by its portrayal in the national media, specifically on NatGeo’s Diggers and Spike TVs Savage Family Diggers. I also addressed some relevant questions regarding why archaeologists may be angry with these “archaeology looter” shows—coming to the conclusion that it is our fault that the average American doesn’t have any idea what we do and why it’s important.)

(In Part 1 of this series, I discussed how the field of archaeology is negatively affected by its portrayal in the national media, specifically on NatGeo’s Diggers and Spike TVs Savage Family Diggers. I also addressed some relevant questions regarding why archaeologists may be angry with these “archaeology looter” shows—coming to the conclusion that it is our fault that the average American doesn’t have any idea what we do and why it’s important.)

Now, I will make a few suggestions on how we can change our perception to the general public.

Almost a decade ago, I remember working at a public museum/ongoing archaeological dig in Fredericksburg, Virginia (called an archaearium by the folks at Jamestown). One sunny, sweltering day, a visitor sauntered over from the McDonalds across the highway from the site. He was sveltely dressed in a sleeveless t-shirt, cargo shorts, flip flops, cheap sunglasses, and a dingy baseball hat. In one hand he had a 44-oz. McSoda. In the other hand he carried a metal detector.

From a distance, the guy looked innocent enough. He was curious and was interested in what we were doing. He’d heard about the archaeology and we were more than willing to discuss our finds (and suggest he go to the main building to pay for admission). After a short conversation covering the usual topics (gold, dinosaurs, Civil War plunder, ect.), he matter-of-factly told us that he was going to do a little metal detecting at the site. He made sure to stress how he’d stay out of the way and pay admission at the main building, because we’d been so accommodating and polite.

I was stunned. When the rage subsided and I was able to speak calmly again, I said, “I’m sorry. You can’t metal detect here. This is an archaeological site and private property. There’s no trespassing and it’s illegal to metal detect for artifacts at an archaeological site.”

“Illegal,” he responded. “No it’s not. I do it all the time around here. I’ve been diggin up Civil War relics all across Fredericksburg for years.” He donned a toothy grin and laughed heartily. “Hell, I’ve even hit some privies in town. Y’all can get some real stuff in them privies. Y’all should go dig there.”

Instead of rage, this time, I just felt numb. Here was a man that was digging up historical deposits all over one of the oldest towns in the United States. He was prolific, looting a number of sites over an untold number of years. I also knew what he was doing was legal on private property as long as he had the owner’s consent. I felt sad for all the deposit that got looted, but I also felt sad that we hadn’t taught this guy that what he was doing was wrong.

The guy probably knew it was illegal to manufacture his own drugs, or drive without insurance, or practice law without a permit, or do dental work without a license. He knew it was illegal to do a host of other professional activities without proper approval, but he didn’t know he was illegal to dig in an archaeological site without a permit.

The public doesn’t know any better!!?!

I know ignorance is no excuse under the law, but it seems like more than 90% of Americans are ignorant about historic preservation, cultural resource management, and heritage conservation law and practice. It could be worse (just check out this article about professional looting in Mali [https://conflictantiquities.wordpress.com/2012/04/03/mali-looting-export-usa-import/]). But, it could also be better (people actually pay to do archaeology in the U.K. [http://digventures.com/]).

While I’m not saying we should dig ever site using avocational laborers, I do think we have an image problem in the United States. Fortunately, I know we can fix it.

The main problem appears to be:

- Everyday Americans don’t know what archaeology is (they immediately think Indiana Jones)

- Archaeologists haven’t taken the time to tell the general public what we do

- As a result, the general public, who pays for most of the archaeology in the United States, thinks we’re comic book characters that aren’t really important.

The easiest way to remedy this situation is to create a bunch of very interested, motivated, local historic preservation advocacy groups that are willing to go to bat for our interests. We need to network amongst ourselves and groups in the general public. It is important to spread the message to children, but it is more important to start friendraising with existing preservation and archaeological advocacy organizations with the goal of creating a motivated network of activists. This community will do most of the work of spreading the word and informing others about what we do.

Effective use of the internet and social media is the best way we can accomplish this campaign. Why? Because the internet is cheap, democratic, and all-seeing. We can target audiences and create better social and organizational networks for pennies than mass media can create using millions of dollars. Social media is like a wildfire that, when properly fanned, can “go viral” and jumpstart movements like no other communications system in history.

Most importantly: all of the tools we need already exist. We just have to use them.

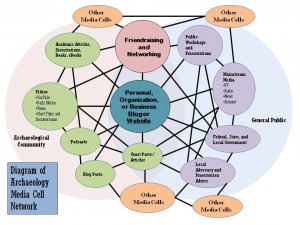

Above is an example of a possible Archaeology Media Cell Network. At first glance, it looks daunting and overwhelming. After you look at it more closely, you can see that this media cell system is actually a web of smaller existing cells that, when synchronized through a website or social media campaign, can create a powerful entity for social change. This network can be used for any number of causes, but it can definitely change the public’s perception of archaeology in a shorter period of time than any of its constituent parts could on their own.

Most experienced archaeologists are familiar with much of this network. Many of us are well-versed in academic writing/publishing, public workshops, working with local preservation groups, and dealing with the mainstream media. However, as a whole, we aren’t as familiar with the strengths of blogging, podcasting, and online video production. And, we are barely scratching the surface of using social media and friendraising to promote our work.

I don’t want to cast myself as an expert, but here are some important avenues we archaeologists can use to change our public image. As you can see below, archaeologists are already active in several of these venues:

Blogging: inter. v.– creating material to maintain a weblog. (from www.thefreedictionary.com/blogging)

Archaeology is just now moving into the blogosphere. The best thing about blogging is it is totally informal, which means everyday people can understand what we’re talking about. It’s also a powerful tool that can be used to create in-depth DIY press releases and opinion pieces that don’t have to get watered down in order to make it past the local newspaper editors. It can also be done comparatively quickly, so the public can be kept up to date with what’s going on in local archaeology and historic preservation news in a timely manner. You can also target keywords to reach certain readers and use

Downsides: It takes a bit of work to keep cranking out material (written pieces, slideshows, videos, podcasts, ect.). You also have to be able to create content with a vernacular/ journalistic bent in order to keep audiences interested. Also, there is no peer-review, so don’t stick your foot in your mouth.

Archaeology Blog Examples: Doug’s Archaeology, Archaeology and Material Culture, Random Acts of Science

Podcast: n.– a multimedia file distributed on the internet for playback on mobile device or computer (from www. thefreedictionary.com/podcast)

Podcasting is another form of content that can be created for blogs or other websites. This is an awesome way to reach people because it can be downloaded and listened to at the user’s leisure and it doesn’t require eye contact so it can be consumed while driving. There are a few great archaeology podcasts out there, but this largely untapped media stream is is growing rapidly. (Chris Webster, creator of the CRM Archaeology Podcast, told me his podcast had over 2,500 downloads in its second month of existence).

Downsides: It takes time to organize and edit the audio files. Contributors must also have some special software and equipment (i.e. headsets with microphone, skype, garage band, iTunes). So, some technical knowledge is necessary.

Archaeology Podcast Examples: Archaeo News Podcast, CRM Archaeology Podcast

Video: We all know what a video is.

With the advent of the smartphone and GoPro camera, archaeologists have more opportunities than ever to record themselves “in action.” Much of archaeological work can be extremely boring, but, with a little knowledge of cinematography and video editing, we can make pretty awesome videos because what we do is so interesting, takes place in remote locations, and is already associated with action heroes. Also, it doesn’t take much for a YouTube video taken in the field to go viral for a number of reasons (good reason: you find something cool; bad reason: you tell the public about something that makes them outraged).

Downside: this can take a lot of time or can take a few minutes. It depends on what you feel is acceptable quality and the length of the film. You can also get in trouble if you film something you aren’t supposed to (Just so you know, it’s bad form to film or photograph burials. Most descendant communities and ethnic groups don’t like it).

Archaeology Video Examples: Past Horizons TV http://www.pasthorizons.tv/

Getting the Word Out and Networking in the 21st Century

If we want to change our perception, we need to follow the playbook of the master: Barack Obama. The Obama presidential campaigns are the best example of how social media, online content creation, and mainstream media manipulation converged to raise a one-term senator from Illinois to the highest office in the land. We may not have the same talent as the Obama campaign, but we can still follow the same playbook (Wanna know what I’m talking about? See “Organizing without an Organization” by Geoff Norquay http://www.earnscliffe.ca/pdf/oct08_norquay.pdf “How Obama Really Did It” by David Talbot http://innovative-analytics.com/docs/HowObamaDidIt.pdf).

Social Media: n.– media used for social interaction that are characterized by highly accessible publishing techniques (from Wikipedia)

Social media is the fuel for our image change network. Websites and applications (apps) like Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, G+ and all the others give us unparalleled opportunities to interact with ourselves and the general public. We need to harness all the connections inherent in social media networking to interact with interested publics that may advocate on our behalf and advertise all the online content we create.

Social media is also a powerful fundraising tool that can crowdsource funds for historic preservation or archaeological work (see DigVentures).

Friendraising: v.– A form of fundraising that emphasizes befriending donors and allied organizations for the purpose of supporting a common cause. Friendraising focuses on establishing friendships and growing networks rather than simply raising money.

Regardless of motive, this is the true power of 21st century advocacy. Friendraising is a networking technique that strives to bring together individuals and organizations from throughout a community and convince them to support a common cause. It is how some of the most successful non-profits create durable organizations that are adamantly supported by local communities. The goal is to make friends rather than just raise money. In the course of building this friendship network, you will also gain more chances for volunteers and donors.

This is a form of person-to-person networking that has been turbocharged by the internet and social media. Since most archaeologists already know about the power of networking for our careers, we can easily use the same techniques to battle public misconceptions about archaeology and protect archaeological sites.

In our case, the goal is to create archaeology “fans” that help us spread the message about what archaeologists do and why it matters to society. We also need fans to bombard network execs whenever they make shows like Diggers. Governments and corporations are more likely to listen to several pumped up advocacy groups that are willing to go to the courts than they are willing to listen to stale, PhD archaeo academics.

What are you going to do?

So, that’s it. That’s all I have to say about that.

I plan on continuing to blog; write academic articles; and contribute to podcasts on CRM archaeology, historic preservation and heritage conservation. I will also keep networking in my local community and giving presentations on archaeology for high schoolers. I will also keep friendraising in order to build my network both online and offline.

The media network system I outline in my diagram is one of many potential systems we can use to combat how we are viewed by the general public. Please, contact me if you have any ideas or would like to know more.

I would really love to hear from you. If you have any questions or comments, write below or send me an email.

Small Archaeology Project Management is now on the Kindle Store. Over 300 copies were sold in the first month! Click Here and see what the buzz is all about

Small Archaeology Project Management is now on the Kindle Store. Over 300 copies were sold in the first month! Click Here and see what the buzz is all about

Learn how my résumé-writing knowledge helped four of my fellow archaeologists land cultural resources jobs in a single week!

Join the Succinct Research email list and receive additional information on the CRM and heritage conservation field.